As an anthropology student, my college professors directed me to archaeology, one of the subfields of anthropology. For historians interested in the colonial period, the last 600 years give or take, written materials are relatively prevalent in comparison to historians of the Bronze Age for example. Meaning that a lot of the history of the colonial period comes from personal accounts that people wrote down. Documents such as an explorer describing the environments in which he wanders or an auditor meticulously notating the conditions of an abandoned home make it into the historical record. Archaeology allows us an opportunity to enhance this knowledge of the past. In historical archaeology, we can compliment what we find from written sources with clues that we find in the ground.

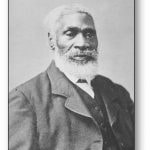

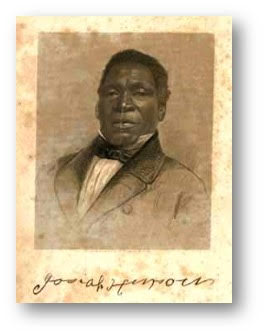

One of the clearest examples of this historical disregard in American History can be examined through the portrayal of Black enslaved laborers. We often think of these people as unintelligent, work-driven individuals; victims of birth into the wrong society in the wrong era. They’re accurately portrayed as victims of systematic violence and coercion but often not much more than that. Where are the stories of their familial relationships, efforts to build solidarity with their peers, resistance or desire to improve their realities? Why are these tales not as common as Columbus’ famous voyage? Largely, as I mentioned earlier, these accounts were not written down and are thus much harder to reveal. Thankfully there are other means of obtaining historical information that can help contextualize what we do know from written sources. I found that archaeology could help reveal the life experiences that I was craving to learn more about. I personally had the privilege of joining an archaeological investigation on the plantation in which Josiah Henson, a formerly enslaved laborer who we happen to know a great deal about, lived for nearly three decades. Henson escaped from slavery to Ontario, Canada along with his family in 1830. About twenty years later, as a free man, he immortalized his life experiences when he published his autobiography, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself.

Through the combination of archaeological, archival and literary research Montgomery Parks is now able to create a museum to honor Henson’s incredible life and disseminate information on the history of slavery in Maryland. And this information is not engaging in a lofty or broad representation of these topics, but instead it will offer detailed accounts of history yielded from thorough research efforts. This form of community engagement allows for the presentation of nuanced portrayals of the lives of enslaved workers and contributes to a deeper understanding of Black History. Montgomery Parks’ archaeological work at the Josiah Henson Special Park is just one of many great examples that exhibit the power of archaeology. About the Author: Craig Stevens, a native of Virginia Beach, Virginia, graduated from American University’s anthropology department in 2017. As a graduate researcher he plans to investigate place-making, identity formation and modes of resistance in the African Diaspora. He will begin his graduate studies through the use of a Marshall Scholarship where he will study archaeology at University College London.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|